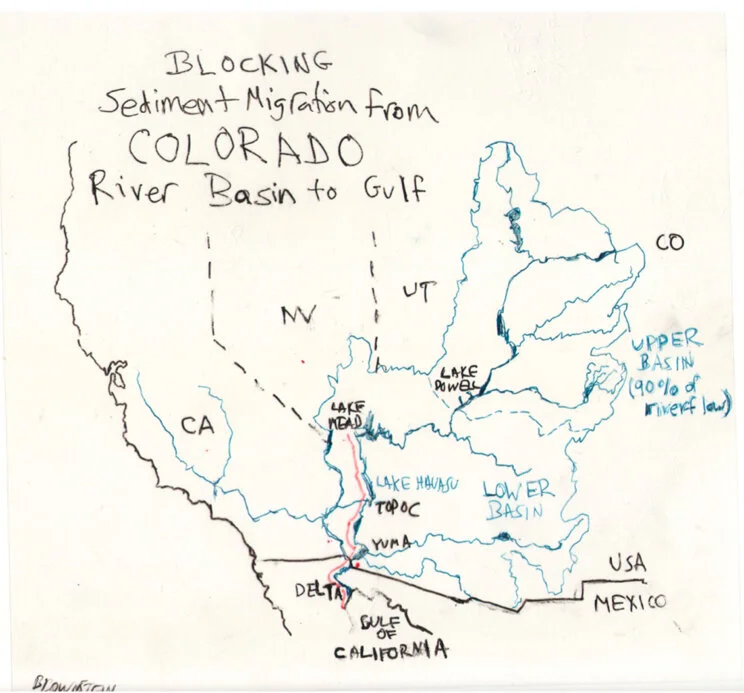

Blocking Sediment Migration from Colorado River Basin to Gulf of California

I didn’t intend to map human migration for the Atlas in a Day project. My plans for a map of the migration of sediment in rivers raised some eyebrows at home, mostly wondering how the subject would fit in an atlas on migration. My wife suggested I ponder the relevance of mineral migration, especially in an age when so many migrants are in need of secure passage. Did the idea of mapping inanimate matter, albeit bearing minerals that were a source of animal and vegetable life, imply a lack of empathy to migrants’ fates, or display a shocking disconnect with the politics of an atlas with such a timely theme? Guerrilla Cartographer Darin Jensen, outlining the project, presented the theme as open to any subject — birds, animals, bees, migrants, ideas, inventions — but sand? “Daddy, make sure you understand the project before you submit your final draft,” my teenager cautiously reminded, apprehensive as she heard me wax poetic on the nourishing natures of coastal California rivers she knew and loved.

The Colorado River proved a perfect topic for sediment migration, I relearned that morning. Its expansive watershed moves sediment across state lines as well as national frontiers, delivering sediment to the Gulf of California, known as the Sea of Cortez prior to the twentieth century. Borders are inherited conventions, imposed on landscapes and encoded in maps. But since World War II, they have become a basis to redirect and apportion waters of the Colorado, motivated in part by the new national protectionism of guarding our frontiers.

Sediment flow in the Colorado River, view from Nankoweap in Marble Canyon, Grand Canyon National Park. Photo by Michael Quinn, NPS.

Redirection of the Colorado’s flow began in the 1930s, at a time of national scarcity, and continued during the 1940s, in ways that had immediate and massive repercussions on sediment flow to the coastal ocean of the Gulf of California. The dramatic closure of the Colorado’s water flow paralleled the remapping of national water rights, and eventually of the continental shelf, which privileged a nation’s exclusive rights to its seabed resources. This broad territorialization of natural resources within state bounds popped out in striking terms as I looked at how the Hoover Dam impacted sediment flow. With President Harry Truman arguing that the nation must defend itself by protecting its seabed resources in the global chessboard of the postwar era, where territorial lines were quickly redefined, watershed flows were recast as national water rights.

The redirection of the waters of the Colorado was ambitious in scope, with several projects damming its flow to irrigate winter lettuce in the Imperial Valley, cantaloupes and melons in Arizona, and beans, green chile, and cotton in New Mexico. The damming projects also created patterns of seasonal human migration from Mexico, formalized in the bracero program. Redirection of water compromised the Colorado Delta, destroying farming communities south of the border and decreasing land values there, while inflating those north of it. The apportionment of water rights from the Colorado, defying the logic of riparian rights, became a new paradigm for dividing water flow in what might be considered the Age of Impoundment, lasting from roughly 1925 to 1970, which saw a worldwide frenzy of dam mega-projects.

At its apex, construction of the Hoover Dam on the Nevada-Arizona border, on the river's main stem in 1936, was the crowning achievement in staking national water rights. This was followed by Imperial Dam in 1938, Parker Dam in 1938, Davis Dam in 1951, and Glen Canyon Dam in 1966 on Lake Powell, as chapters in the massive project of creating farming lands and redirecting — or blocking and obstructing — historical sediment flow.

The Colorado’s expansive Upper Basin, sprawling across the states of Colorado and Utah, drains 90% of the waters that once flowed so abundantly south at a rate of almost 400,000 cubic feet/second in the late nineteenth century. The Hoover dam redirected a monumental 3.25 million cubic yards of water, and in its immensity, became a symbol of the nation’s power and prosperity.

Hoover Dam, April 2019 (photo by the author)

The massive dam plundered the waters of the Colorado, the “American Nile,” as a resource to irrigate farmlands in Arizona, California, and Nevada, which were promised in the concordat of 1928 to receive 37.3%, 58.7%, and 4%, respectively, of the redirected water. This bounty, however, ended the flow of suspended sediment flowing south or the border. The Hoover Dam, which imposed this uneven trade-off, is shown as a red dot in my map of Blocking Sediment Migration.

The line on the map represents the nourishment of the riverbed ecology that distinguished the habitat of the Colorado. When naturalist Aldo Leopold navigated the Colorado’s sand bars by canoe in 1922, he marveled at the wealth of natural life that “had lain forgotten since Hernando de Alarcón landed there in 1540.” It supported an abundance of life that populated the Colorado River delta in “lagoons so diverse in wildlife — egrets, cormorants, skittering mullets, mallards, wigeons and coyote, as well as jaguar.” To Leopold, the Colorado River was both “nowhere and everywhere,” containing hundreds of green lagoons that led to the pristine wilderness of the Delta, enriched with annual spring flooding that ended just fourteen years after he explored it, as the flow of sediment that offered food supplies for native humpback chub, razorback sucker, and seabirds was curtailed.

The obstruction of all that sediment from the powerful flow of winter snowfall across the Colorado Upper Basin, which melted at a rate of 100,000 cu ft/sec, effectively ended the natural wealth of a region that oceanographer Jacques Cousteau christened “the world's aquarium,” and with it the economies, ecosystems, and agriculture of the delta lands. Prior to the dams, the river sediment supported many productive farms near its delta, once farmed by Cocopah Indians. The small community of farmers living on the Hardy River — the remaining trickle of the Colorado that only sometimes reaches the Gulf — has been reduced to only 200 – 300 today.

Map by David Lindroth, Inc., Copyright Yale Environment 360

The problems of mapping sediment flow are profound: the issue lies in the nature of data collection, and the difficulties of smoothing data from river sampling stations, tabulated by different folks, to create a compelling graphic record of sediment flow. USGS sampling stations were seasonal, measured differently if with regularity, and offer quantitative challenges, making it difficult to compare the earlier flow to the amounts of sediment cumulatively trapped behind dams.

In light of this, I reconsidered the mapping of sediment impoundment as a human intervention, haunted by a near-obsession with the recent political mismapping of “illegal” immigration. The idea of mapping sediment as a problem of migration across national divides became a map of blocked migration. “The Hoover Dam is the exact precedent to the Border Wall,” I said to two Guerrilla Cartographers at my table in Oakstop, and they nodded in affirmation.

The human side of the Hoover Dam story is the rise of seasonal migration to work the fields the dam made possible. The diversion of the Colorado allowed irrigation projects from Nevada to the Imperial Valley, creating a massive market for the migration of cheap agricultural labor. A series of laws and unilaterally dictated diplomatic agreements, initiated August 4, 1942, structured the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement and set the pattern for northward human migration and hemispheric economic dependence that persists to this day. No map of hydro-engineering is complete without the story of migrant labor movement that it created, but that story has been regularly ignored in maps of water diversion. Mapping the blockage of southward sediment migration makes clear the structural parallel between dam arch and border wall.

In the map, I marked the extent of impoundment by a red line engraved into the landscape, a disruption of sediment flow, to remap what was more often celebrated as an engineering feat of controlling water flow around the border. Suspended sediment in the Colorado declined tenfold in its annual tonnage in the 1930s, with maximum loads of suspended sediment at Topock, AZ dropping from 7.64 - 20.6 million tons/day to half a million.

The USGS had effectively tabulated the range of sediment the Colorado carried south from Lake Mead. C.S. Howard compiled readily available USGS data of suspended sediment in the River through 1941, based on a survey of sampling stations below Lake Mead, reflecting conditions before the dams across the Upper Basin and Lower Basin of the Colorado. The gloriously retro USGS map that Howard used to locate the gauges afforded a base-map for my own map, which would contrast the line of the stopped flow of sediment with the dot where the first section of the Border Wall has been built.

USGS Survey Stations, Suspended Sediment in the Colorado River 1925-41

The final version of the map, drawn on a transparency, was rough: it needed to show the rivers that lead to, and the watershed of, the Colorado River in bright blue, with a line of blocked sediment to the Gulf rendered in red, against its expansive watershed.

The coastal ocean is not depicted in my map — and if we had over a day to create a map, the delta would merit closer detail. Some restoration of the Delta was recently allowed by water treaty modifications adopted in September 2017, ensuring a continuous flow of river water to the Delta to regrow its habitat. But the picture of blocked migration is clear, and the red dot stands in a provocative symbolic dance with that red line, making us reflect on the power of maps and mapping borders and boundaries.

The diversion of water was a massive story that had been told, but at a time when the Colorado no longer reaches the sea, I wanted viewers of my map to consider the parallels between the paranoia of blocking human migration and the power fixation of diverting water away from natural migratory paths. But as even Lake Mead today faces the prospect of going dry, the impounded sediment has been dispersed to the north, its nutrients never able to reach the shore.

Damming the flow of the Colorado River demands to be understood as a project controlling the movement across borders, and dictating regional ecologies from behind borderlines. Seen through this lens, wasn’t the Hoover Dam, as much as any other structure, the model for the unilateral control over migration, whose ambitions are today recapitulated in the Border Wall?