Guerrilla Cartography aims to promote the understanding that there are many views of the world, that how we understand space and place can vary, and that we should think critically about the maps and the graphics we make and consume. Our organization has designed processes for creating our atlases that support these goals.

1) By Featuring Diverse Narrative Viewpoints

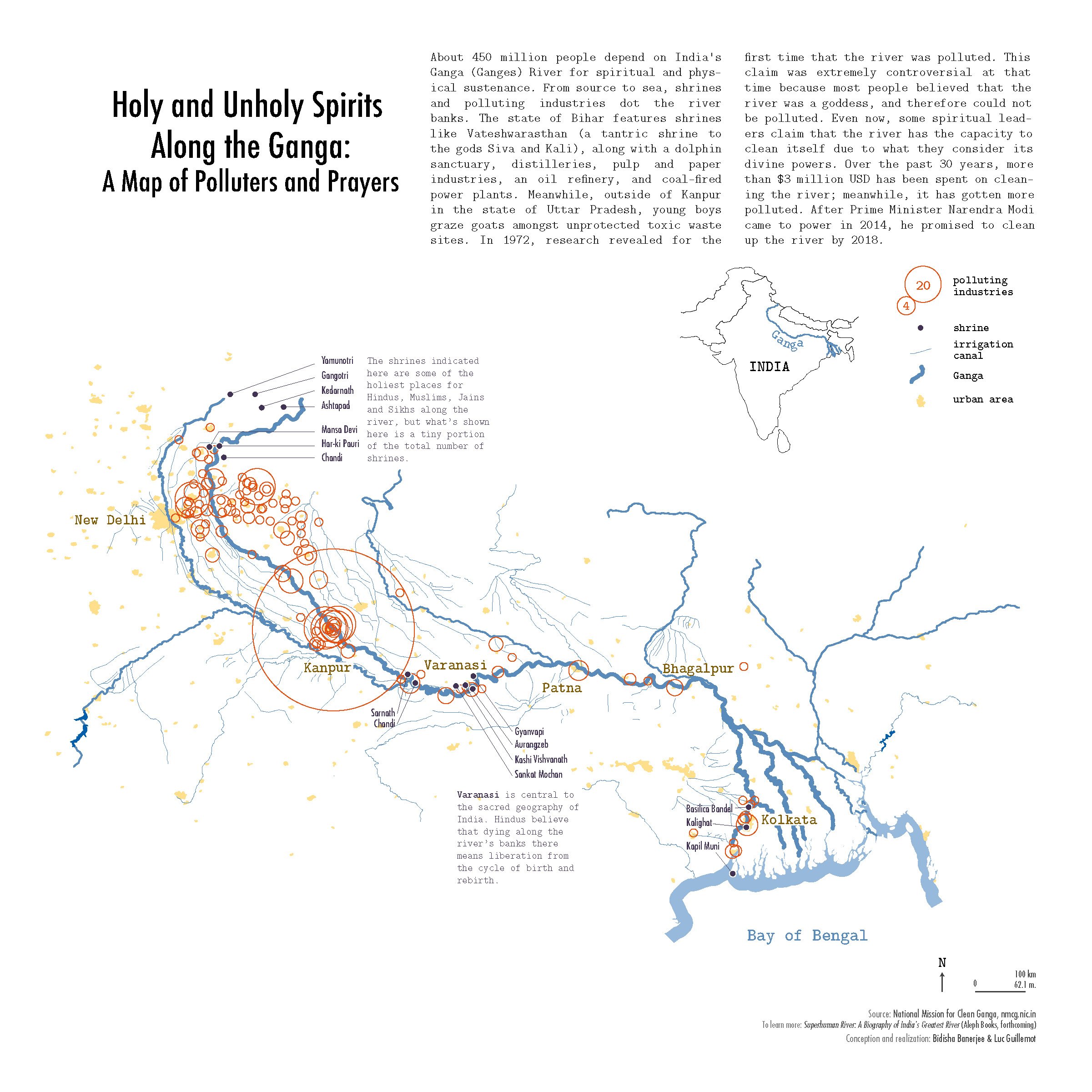

A different person or group of people produced nearly every map in our atlases, each contributing their individual aesthetic and experiences to the broad theme. We can never tell all stories about food or water, but crowdsourcing content allows us to glimpse a few things that we might not otherwise encounter, giving the atlases a variety of perspectives. An example of an unusual narrative viewpoint is the map “Holy and Unholy Spirits Along the Ganga: A Map of Polluters and Prayers,” which juxtaposes spiritual sites with polluting industries along the Ganga (Ganges) River in India. This map was a collaboration between social ecologist Bidisha Banerjee and cartographer Luc Guillemot for Water: An Atlas.

Holy and Unholy Spirits Along the Ganga: A Map of Polluters and Prayers by Bidisha Banerjee and Luc Guillemot in Water: An Atlas (2017).

The atlases also exhibit a variety of literal viewpoints, including different projections and scales. One example is Garrett Bradford’s map of “Global Almond Trade and California,” featured in Food: An Atlas.

Global Almond Trade and California by Garrett Bradford in Food: An Atlas (2013).

The central map employs the unusual Peirce quincuncial projection in order to place California at the bottom, so as to better showcase the almond trade that emanates from it. The cartographic choices highlight the narrative of California as the center of global almond production.

2) By Placing Maps in Relationship to Other Maps and Information

The atlases are meant to be both informational and entertaining, readily accessible to anyone with an interest in maps, in the theme, or both. After the call for maps is sent out, the maps that the crowd chooses to make end up creating a narrative for the atlas. We do not prescribe the narrative in advance; it grows organically throughout the process of building the atlas. We are then able to group the maps into narrower themes within the broad theme, giving a structure that makes the atlas more than simply a collection.

This is the part of the atlas that is editorial, and that makes the board a part of each map and its story. While each map by itself has a story, that story also becomes contextualized in the order of the maps. We experiment with multiple linear “stories” as we work to pull the narrative thread through the atlas. There are other stories that can be told with these maps and other ways they could be grouped, but due to the constraints of producing a physical atlas, the editorial board decides the final grouping and order for the maps. We hope our arrangement of the maps provokes a response in readers, prompting them to agree with or question the narrative that is being told, and to translate that to their viewing of other maps and atlases.

3) By Building Legitimacy for Marginal or Atypical Cartographic Voices

Among other things, Guerrilla Cartography is concerned with authority — the authority of who gets to produce and distribute maps and why. The narrative construction of the atlas and the editing process itself both help give legitimacy to voices that may not have access to traditional atlas or map publishing venues. Our process of pairing people who have map ideas with our volunteer cartographers is another way that we make space for many different viewpoints, such as the collaboration mentioned above for “Holy and Unholy Spirits Along the Ganga.” Banerjee had been immersed in a project about the Ganga since 2009; after submitting her idea to the Water: An Atlas call for maps, we connected her with Luc Guillemot, a Guerrilla Cartography volunteer. They worked together over email to bring Banerjee's vision to life.

Seeing the ways that a variety of people represent geographic data is informative and instructional. While anyone can publish maps that they have created on the Internet, distribution may be limited. Without a digital home, these maps may also disappear. Guerrilla Cartography’s atlas publishing model enables a broader audience and a more concrete presence-both digital and physical. The crowdsourced nature of Guerrilla Cartography’s atlases also helps viewers critically examine their assumptions of who has the authority to produce maps.

4) By Promoting Critical Evaluation of Content, Authorship, and Authority

The myriad styles, narratives, and scales of the maps contained within Guerrilla Cartography’s atlases invite readers to question their assumptions about how a map is constructed, by whom, and for what purposes. The atlases also encourage readers to think critically about the very data that the map representations are constructed upon. For instance, in Water: An Atlas, we open with a chapter titled “Imagination.” Here we are mapping imaginary data, or in some cases actual data on imaginary or legendary phenomena. The map “North American Water Tensions in the Year 2028,” for example, depicts a dystopian vision of water scarcity-caused conflicts in the not-too-distant future.

North American Water Tensions in the Year 2028 by Bryce Touchstone and Melissa Brooks, in Water: An Atlas (2017).

For someone to read these maps, they must begin to understand that, while the map portrays a certain authority, the mapped data may not exist in the real, tangible world. Unreal data are being mapped. What does that mean for all the maps we see? Does it make us wonder about the “real” data that are being mapped elsewhere in the atlas?

Alicia Cowart and Susan Powell are members of Guerrilla Cartography’s Board of Directors. An expanded version of this article was first published in Cartographic Perspectives, Number 92, 2019.