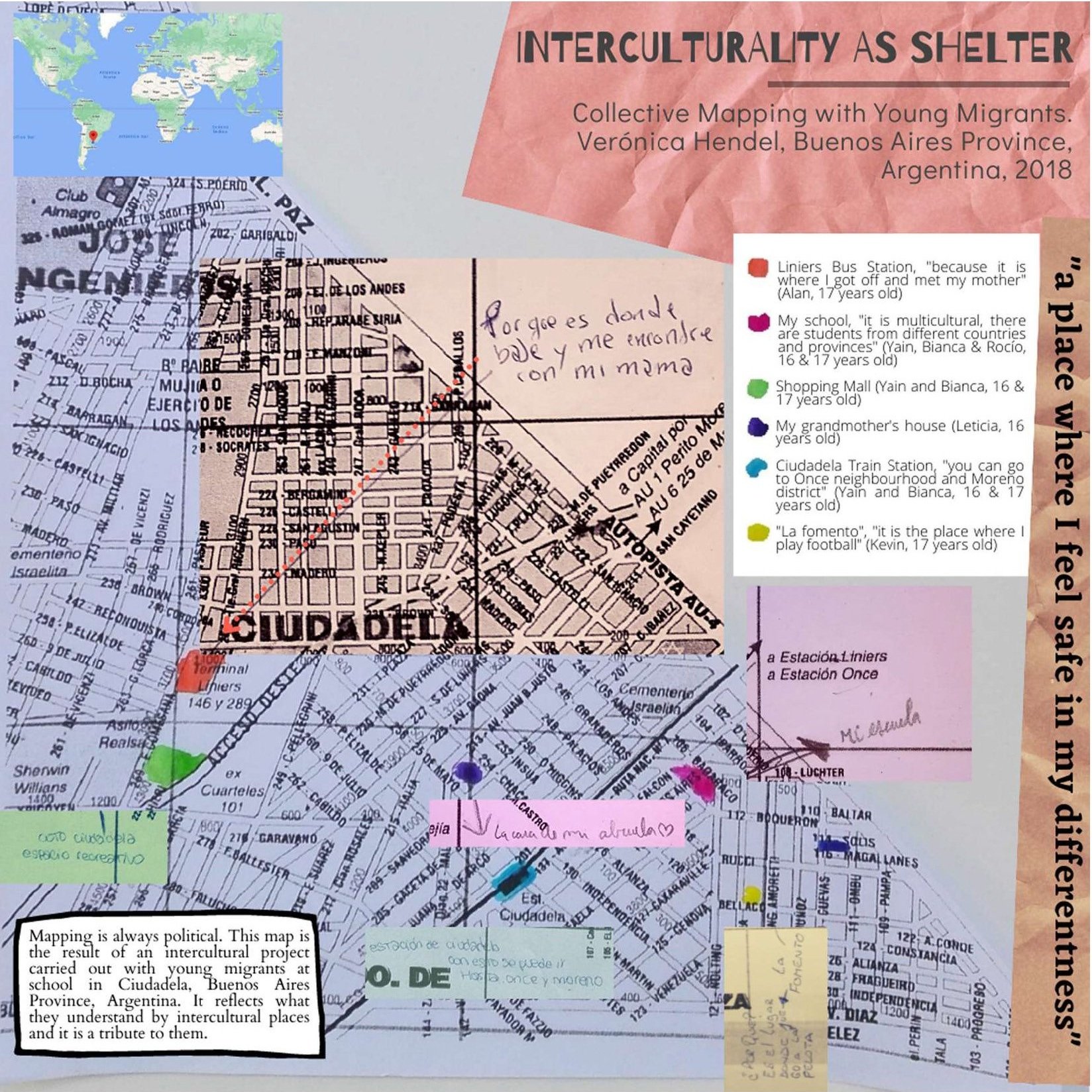

Interculturality as Shelter is a map made of many maps. It examines the ways in which young migrants experience interculturality in the neighborhood where their school is located. It shows their ways of feeling, walking, and making the city.

A neighborhood where nobody cares

Ciudadela is a town located in the southern part of the Buenos Aires province district of Tres de Febrero, Greater Buenos Aires, Argentina. It is a place of passage, circulation, trade, and exchange. Located halfway between one of the most important train stations and bus terminals in Buenos Aires City, and the train station that bears the name of the neighborhood (located in Greater Buenos Aires), Ciudadela unfolds as a diverse, heterogeneous, unequal, and insecure space. A territory that is home to many others: Ciudadela Norte, Ciudadela Sur, Villa de los Paraguayos, Fuerte Apache, Villa Herminia, Villa de los Rusos, and Villa Matienzo, among others. Places that bear ethnic, class, race, and national marks in their names that refer us to historical formations of otherness.

As young people themselves point out, they “come from many trips.” Mobility takes place in the context of family migration, involving multiple movements between countries (in general, Bolivia and Argentina, but also Paraguay and Peru), provinces, cities, and/or neighborhoods. The multiple mobility experiences of these young people are, in turn, experiences of diverse territories and multiple border crossings, an extremely relevant aspect when reconstructing and analyzing their experience of the city.

“Why is our neighborhood dangerous? Why can’t we walk without feeling fear? How did the neighborhood come to be what it is?” are some of the questions that young people framed in the context of an ethnographic and collaborative work experience carried out in a secondary school in Greater Buenos Aires (Argentina) between 2018 and 2019.

In this sense, displacement cuts across this map in various ways. First, as a way of inhabiting, traveling, and “making” the city of the young people with whom we worked. Second, as a broader repertoire in their experiences of multiple territories linked to the migrant condition of most of them. Finally, as an activity or operation subject to control or “government” by the State, and specifically by security forces in urban space.

Interculturality as Shelter shows the backside of this experience of the city as danger. Interculturality is a complex term that young people were debating at school in the context of a broader project. When I asked them what they meant by it, words such as “respect,” “tolerance,” and “cultures” emerged. When I told them about the idea of mapping interculturality, new aspects came to light: political and affective dimensions that were not visible before. It was the first time they carried out such a mapping experience.

Taking an official map as a departure point was a limit but also a good opportunity to point out the tensions between their lived experience of the city and the one cartographers took into account. It was hard for young people to place themselves into the maps and find those places they linked to interculturality. Most of them worked in small groups but others preferred to do it individually. Part of my challenge in doing this map was to turn the eight maps I received into only one.

Three of the eight maps that were combined into the final map.

Mapping is always political

Far from notions such as tolerance and respect, when mapping, young people link interculturality to places where they feel safe among others, such as friends and relatives. Places where they feel safe in their differentness.

The production of other cartographies and maps enabled the creation of spaces for dialogue and the production of collective knowledge about the experience of the city. Reflection from a visual device allowed the articulation of ways of experiencing the city and narratives that dispute, and challenge hegemonic urban perspectives.

The Interculturality as Shelter map appeared in Shelter: An Atlas, published by Guerrilla Cartography in March, 2023.