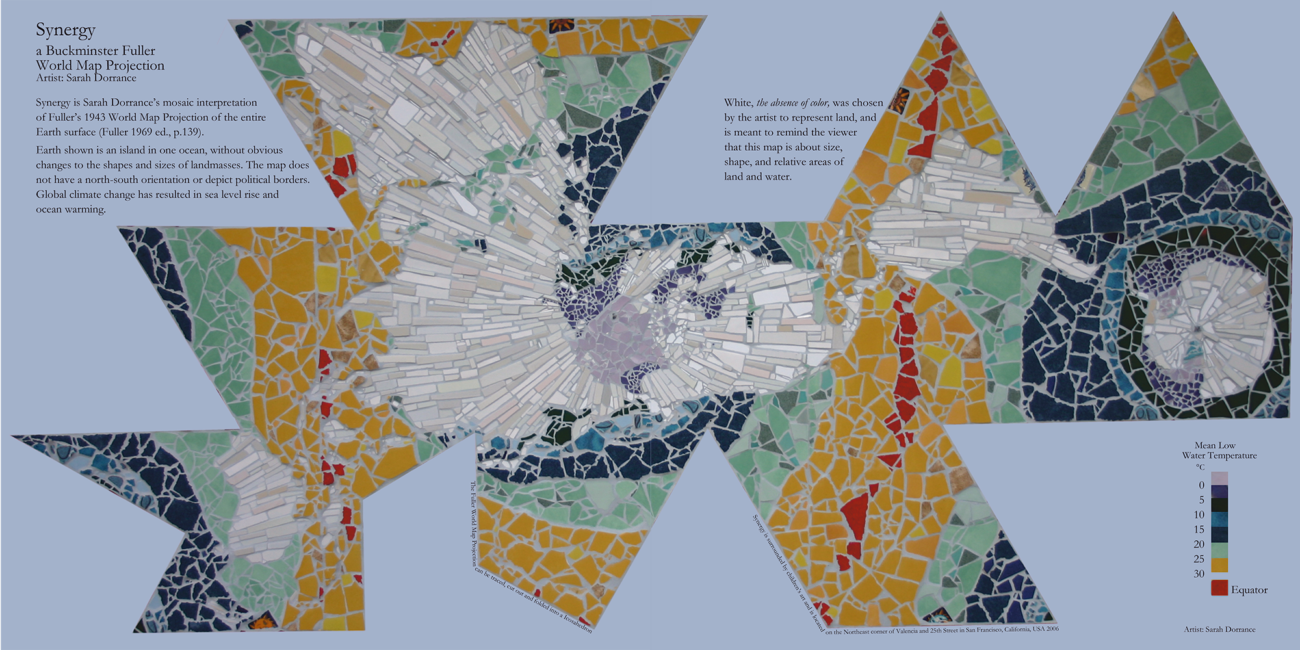

My mosaic work is about nature —water— with some obvious maps. Whether it is the Fuller Map, the John Muir Woods Map, or the Ansel Adams Wilderness Topographical Map, mermaids reading books, houses, maps and water run through my work.

After discussing the idea of participating in this collaboration with one of my muses, I write and ponder my work.

How did you decide to map what you did for Water: An Atlas?

Specifically, this piece was created as part of a larger work in which most of the artists were young students in school learning to do mosaic. Schools around the world tend to teach young students with a map that places north to the top, and the country the school is from in the center of the world. The Fuller Map puts the land mass of the Earth in the center, surrounded by water. North and south are only subtly referenced with longitudinal lines, and the concept of North being up or down becomes nonsensical.

It occurred to me that this map was a good lesson for the students, people of the city, and visitors from everywhere who might walk by it. I realized in making the map that my personal work was at times north-centric; I live in North America. I further decided to make the land mass white, emphasizing the unity of all the earth, but make the water colored according to the temperature map at the time the original version was created. With global climate change, this was already incorrect by the time the mosaic was made. When the invitation from Guerrilla Cartography came, transforming this physical mosaic map into an electronic map for the book came quickly to mind.

What was your mapmaking process for this map?

The process for making the original mosaic was to transfer the original map as a sketch onto sheets of cement backer board, then creating a mosaic in the traditional, direct method using found, used, donated tiles and snapping them to exactly fit accounting for grout lines.

The creation of the electronic map involved taking many pictures and using software to subtract surrounding art, which is not the map.

Generally, I roll many ideas or concepts in my head, and then into words, and then out loud so the folks that inspire my work can give me their thoughts and ideas. And then I look for the strands that carry me to my concept. This process lead to the map.

For me this is a wonderful part of making my art, whether I am collaborating (I’m always collaborating) with David Kardatzke, the Maynes brothers Cyrus and Emery, or Peter Chartrand of Bisbee Clay on a current work in progress, titled, “Tres sirenas con libros en la desierta” or working with GC or with myself in my studio, I love hearing what others are thinking about how I might convey my message and their message also.

I consider these folks an integral part of my work, they are my muses. Accomplished people and artists, scientists/geographers, thinkers and ‘understanders’ of the Importance of the Earth. These are the people who understand me in their own way, they influence my work.

What surprised you during the map-making process for this map?

How hard the computer/electronic manipulation process was, compared to the apparently more difficult physical process of snapping tile and fitting together a large physical mosaic.

How do you hope this map might affect people, or how might they use it?

I hope they might see that they are part of a single world; they are in it together with the other humans, animals, plants, oceans, etc.; and they recognize that some of us humans are choosing to change the world in a very dramatic and destructive way that is not benefiting others or even ourselves in the not-so-very-long run.

It may take a bit of sleuthing to understand my work. Part of my message to the observer is to look at art, really sit and ponder it. I do not really believe radical change occurs with only a surface understanding.

I consider all of my mosaic work to be various kinds of maps with a message from the artist, even if the work is a butterfly or mermaid. When my work is considered as a whole, the meaning becomes clearer that my work is about mapping our environment.

What does it mean to you to be a “guerrilla cartographer?”

Being a guerrilla implies engaging in irregular, unconventional, radical, assertive actions. To me, a guerrilla never acts without purpose, To be a guerrilla, a person has thought about things and decided the usual approach will not work — something else must be done. This means there is a purpose, something to be achieved, a radical transformation to reach. A Guerrilla Cartographer is trying to use mapping in a new way, to effect an understanding that triggers this radical transformation of the world. One of the best parts of participating in this project was reviewing and commenting on the other maps and experiencing the radical transformation that they inspired. GC in my mind is a form of irregular cartography because it includes artists, cartographers, and geographers, encouraging discourse from around the world. It seeks a revolutionary change in a person’s mind, I consider myself a Guerrilla Cartographer and GC is a muse with many voices. I am influenced by the conversation GC creates, which includes art as important maps, and maps as important art.

GC puts out an idea, inviting participation in a collaboration, and I am compelled to participate!

GC grows my understanding of my personal message.

— Sarah Dorrance