How did you decide to map what you mapped for Water: An Atlas?

“Water has a habit of finding me. If I am not long-boarding in cold Atlantic water, swimming in lochs or encouraging kids to jump in, I am sitting in proximity to it, letting it speak. Let’s face it, it is life and the thing that unites us with all other life forms.

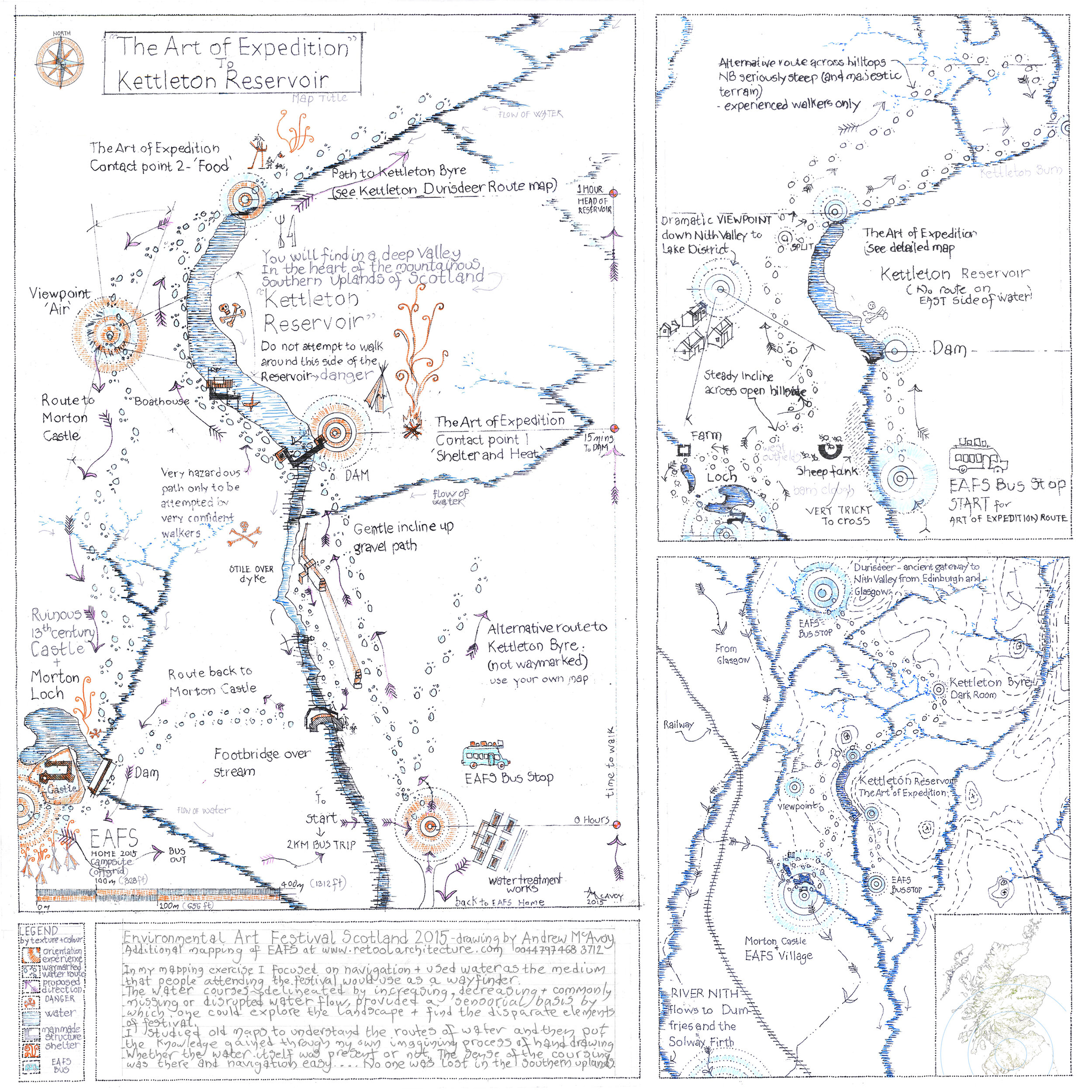

Key to the Environmental Arts Festival in Scotland (EAFS) was expedition into unknown territory in the Southern Uplands of Scotland. Explanation of context and clarity in way-finding were critical. I was asked to help unfamiliar people navigate a huge landscape with a makeshift biannual and changing festival site at its central point. Radiating out from the site there was one constant – water – and I immediately jumped to that as the navigation tool.

I leaned on a local artist and festival organiser, Matt Baker, for where to place emphasis and for focussing of mapping toward the realities of intense human interaction. I walked in the landscape with Berlin artist, Andreas Templin, who encouraged acceptance of abstract process.

What was your mapmaking process for this map?

Working as an architect through the medium of deep context, I am used to searching for what I call buried landscape narrative. I commonly start what will become a futuristic project imbedded in the possibilities in place and climate, by visiting libraries to look at old maps. I do this as far back through time as possible until I have its sense, then I acknowledge the present and then vision the future.

In the case of EAFS, I requested all the old ordnance surveys, reviewed them and started to trace the contours that clearly illustrated the glacial scars and cuts made by water over time – water that had passed over soft and hard geology. That provided a guide to where water was falling from, its route and tributaries, and commonly highlighted where man’s interventions had changed its course. The sources all ended up from one outer extreme or watershed leading to the EAFS 2015 central site and the hive of festival activity.

Scotland has a lot of water, the Southern Uplands follows Scotland’s trend and water coursing was easy to draw by hand over old maps as tracings. Equally general tendencies to divert it, exclude it and make it go away were simple to map and in the end everything joined up. The maps enabled people to set out from the site on 20 km round trips and easily way-find with flowing water in their view or the sense of where once it had flowed.

What surprised you during the map-making process for this map?

I was struck by how the effects of geology – glacial scrape 10,000 years ago and the continued presence of water coursing down decreasing contours toward valley floor level – had been used historically toward navigation. Quite commonly, the route to high ground and pathways across whole regions used for centuries were a parallel act to the coursing of water. A few meters above high-water mark and making gentle use of the contours, our forefathers had created paths.

By tracing the water or the ghost of it, I was giving the navigator something tangibly perceptible.

Water was the navigator and the cartographer itself. I was just the Guerrilla, hijacking what nature and sentient humans had done already. As cartographer, I was only giving what was there some graphite emphasis.

How do you hope this map might affect people or how might they use it?

I hoped that no one was lost in the Southern Uplands at Festival time, and no one was.

The process highlighted for me that water knows no bounds, it navigates by gravity seaward. With our ice caps melting we all need to take cognisance of our needs to prevent sea-level rise and to play our part in the delicate balance of our planet’s mantle.

I hope people looking at the maps see that we are all linked in one atmospheric condition, in one earth-wide pull and push. Modern physics gives us a sense that the minuscule movement of one butterfly wing on one side of the earth is related to a tsunami somewhere else on the other side of the earth.

I hope that the EAFS mapping contributes in a tiny way to greater understanding that our resources are finite and precious, and that abuse affects someone else further down the contours.

What does it mean to you to be a “Guerrilla Cartographer?”

To be a Guerrilla Cartographer is to be able to select your own content, to map what you see to be the potential in landscape and not to accept commonly upheld or promoted narratives on people, place and environment, which are commonly 99.9 % lies and misconception due to distortion.

For me, it reaffirms that there is a lot left to map, that our planet is precious, that I am lucky it provides trees and paper, that I must harness a little more time to be cognisant, and yes, it gives me license to burn a little graphite. It may even lead to my ten-year-old daughter picking up a pencil amidst her generation’s realignment of humanity with nature.